Generalists vs Specialists [Part 2]

Practical answers from the academic literature — Who gets paid more? Who gets hired more? Which one should I hire? and more...

Hey friends,

Last week’s newsletter about generalists vs specialists led to an abundance of quality conversations. Although my default is to try and explore topics open-handedly, cultivate curiosity, and make surprising connections across unexpected categories; I realized that there is a lot of research on this topic and, therefore, a lot of space for practical advice. As a result, I want to be more concrete this week and give solid answers to the questions that a lot of people are asking about the generalist versus specialist divide.

While all this research needs to be taken with a grain of salt and weighed against the fact that it is speaking about averages only, the following newsletter is a good synthesis of a couple hundred pages of academic and professional literature that I reviewed just for you. So, without further ado…

Generalist vs Specialist Defined

A specialist is a professional who focuses on developing deep expertise and high proficiency in a very specific area or field. Specialists spend significant time mastering one subject or skill, making them experts in a narrow domain. This allows them to solve highly complex and niche problems within their area of expertise. They are often in contexts with high division of labor, where they fulfill a very precise function before passing along their work to another individual.

A generalist is a professional with a wide range of skills and a breadth of knowledge across multiple disciplines. Generalists spend time exposing themselves to new challenges and engaging with situations that have minimal contextual overlap. This allows them to better navigate uncertainty and translate the needs, language, and strategies of various categories across multiple scenarios. They are often in spaces with low division of labor or that have more ambiguous job descriptions. They are rarely confined to a single point of the product or service lifecycle.

Generalist vs Specialist Destigmatized

As I mentioned in my first post, I like to think of the two postures as deep and wide. Yet, it’s important to note that being wide does not necessarily mean being shallow, and being deep does not necessarily imply intellectual superiority. Although I will put forward some pretty stark realities from a professional development perspective, there is no a priori evaluation metric that makes one category “better” than the other — both are necessary and exist as a regular part of the professional world.

A fantastic example can be seen with doctors, who literally divide themselves into categories of specialists and generalists. General practitioners, for instance, dedicate themselves to over a decade’s worth of education, residency, and certification, in order to adequately treat a broad range of symptoms that might emerge from a variety of different patients. Specialists, on the other hand, go through more exact training in order to better understand the complexity of a singular disease or illness. Specialists only deal with one kind of patient with one particular challenge, but go through even more schooling, fellowships, and certifications than the generalists. In both cases, however, the development of their expertise is arduous and the importance of their practice is best evaluated by the patient they are treating. As one family practitioner wrote in defense of their discipline:

Is [our profession] defined by the size of our basket of services or by the range of ideas and experiences at our disposal?”

Enough said. Now, let’s jump into the data.

The Facts

On average, people who want to maximize their earning potential and increase their own job prospects should overwhelmingly strive to be generalists. The studies are clear that, on average, generalists are not only hired at a premium when compared to specialists, but that companies favor generalists over specialists in the hiring process. One study that analyzed the skills and compensation of all the CEO’s in the S&P 500 companies over 15 years found the following:

A generalist CEO earns about 19% more than a specialist CEO, which in dollar terms is about $850,000 per year.

And this is not just true for CEO’s. While the size of the premium shrinks or expands depending on precise title, tasks, industry, etc… the rule still holds in a majority of contexts. In fact, one study deemed this concept the generalist bias, referring to an organization's tendency to reward and select people with general skills even when complementary, specialized skills would have been more productive. Another study corroborates:

Generalists in an online labor market earn higher wages than specialists, particularly when generalists can combine multiple skills... and MBA graduates with generalist profiles receive more job offers and greater bonuses than MBA graduates with specialist profiles.

Although this may be surprising to you — it certainly was to me — the logic becomes clear after we grasp a few key concepts.

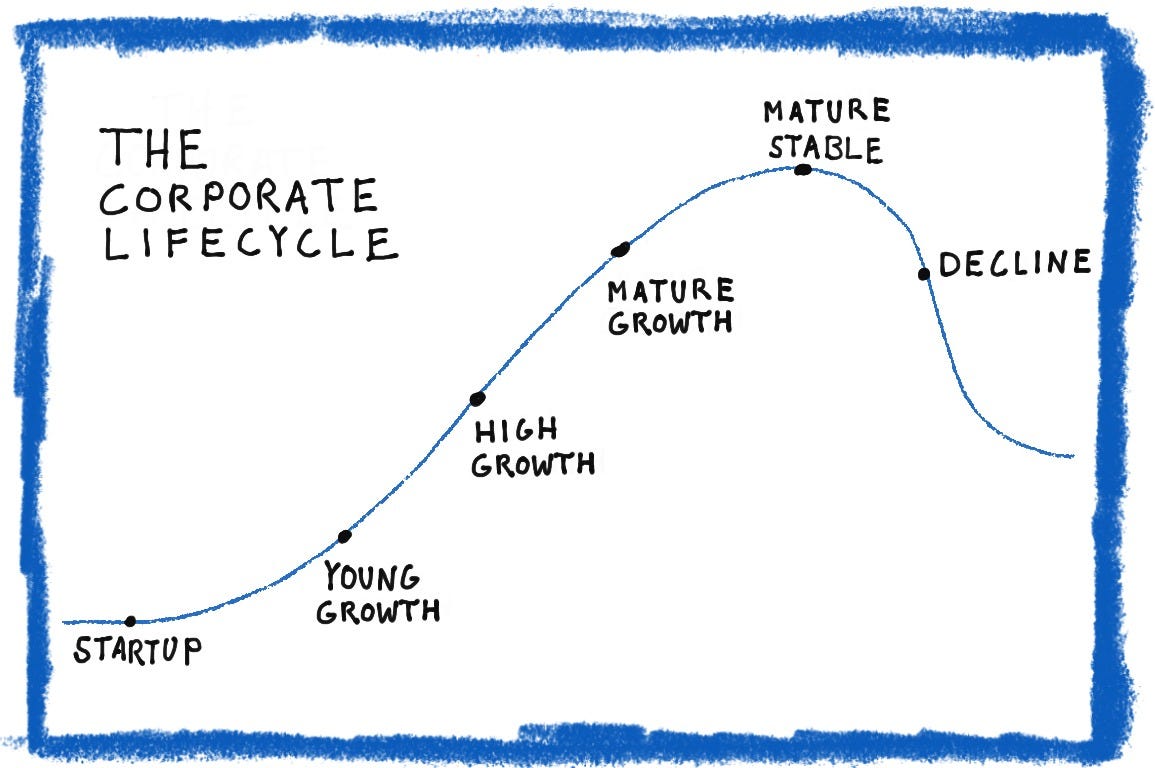

1) Cradle to Crypt

Firstly, generalists are needed at every stage of a company’s life cycle, but the same cannot be said for specialists. In the beginning years of a startup, individuals are expected to wear several hats as the team is small and resources are scarce. This is why entrepreneurs and early hires tend to be more generalist — because they are forced to be their own HR, Accounting, Marketing, Operations, and Legal department. Yet, even as a company grows and adds more specialists, the need for generalists to manage the workflows and connect the specialists continues to grow in tandem. Ergo, the majority of executive and managerial positions (which tend to get higher pay) are filled with generalists who can bridge the various disciplines, departments, and organizational needs.

Interestingly enough, the literature does show that specialist workers, relative to generalists, obtain more promotions — but only late in their careers. Why is this the case? One argument is that large corporations who can afford to specialize are forced to formalize their processes and create clear pathways for advancement. But, by definition, specialists only gain credibility and recognition after spending lots of time in a particular field.

We also know that people with generalist skills tend to relocate between firms more frequently than specialists, which affects the duration of time they are in a company and therefore the number of times they are eligible to receive internal promotions.

2) Transferable Knowledge Really Matters

Secondly, specialist work is confined to a narrow context and typically involves a workflow that is specifically constructed to facilitate that specialist’s unique needs. While the knowledge might be exclusive and therefore seem valuable, this is actually a double-edged sword that can hurt the specialists’ job prospects and professional leverage.

Since the specialists’ experience is so context-driven, the number of possible positions that a specialist can occupy elsewhere are lower than a generalists’. Plus, specialists often struggle to perform at the same level of excellence when moved to a different team, department, or company; research shows that productivity levels drop the most when an outsider specialist is brought into a new company, as opposed to a more minor drop when generalists are brought in. Plus, generalists are more likely than specialists to transfer useful knowledge to new environments because specialists lacked exposure to tasks and activities outside their unique purview and are also exposed to less of the new organization than generalists.

Now, this does not mean that filling an organization with generalists is better than filling it with specialists. In fact, the research is very clear that overgeneralizing leaves a lot of value on the table — and leaves specialists under-compensated and under-appreciated. The trick is to find a proper balance of specialists and generalists while still giving all members (but especially specialists) ample support:

Specialization and coordination interact to predict performance. The best performing groups are high both in specialization and coordination. The worst performing groups are members who were high in specialization but were not able to coordinate their activities.

This links us back to point number one — greater specialism requires greater coordination. As specialism increases, so does the need for coordination. Yet, decreasing specialism in order to keep things more general, and therefore more manageable, sacrifices potential performance gains. Specialism can either be the best of the best or the worst of the worst. This leads us to our third point.

3) Yearning For Resilience

The demand for generalists is very connected to an organization’s macro-environment, as is the optimal mix of specialists to generalists. One study discovered this very useful insight, which has become more and more common with each passing year:

The generalist pay premium is pervasive across industries, but it is higher in industries that have experienced regulatory and technological shocks in the last two decades.

The same study also found that firms with poorer accounting performance (like lower profitability or plummeting stocks) before a CEO transition are more likely to appoint a generalist as the new CEO rather than a specialist. Together, these tidbits give us a clear window into the psychology of recruitment officers and board members; people are gravitating towards generalists because they see generalists as a means to cushion themselves from the effects of uncertainty. When bosses don’t know what the future holds or when they feel burned by having previously put all their eggs in the specialist basket, hiring a generalist who can “do it all” seems like a safer bet.

In investment terms, generalists are the employee equivalent of ETF’s and mutual funds. Their portfolio of skills is diversified, meaning they don’t crash every time the market is upset or gets disrupted. In today’s atmosphere of volatility and unpredictability, companies are looking for anything that will help build resilience and flexibility into the fabric of their organization — and generalists are the types of employees that absorb the shock.

What This Means For You

Thoughts For Generalists

My review of this research has actually made me more confident in the advice I shared in the last newsletter. Molly Graham, Tim Ferriss, and Peter Drucker each, in their own way, advocated for something similar to the “old but gold” concept popularized by IDEO and McKinsey regarding T-shaped individuals—people who are able to combine the best of both breadth and depth. Now more than ever its important that workers are able to find the overlap between their most valuable competencies and distill it into an easily-proven, highly articulable description of what they do… but also construct this description with the knowledge that bosses are biased towards descriptions that convey a spray of general functions.

Moreover, in a world where generalism is in vogue, one of the biggest threats to personal efficacy is the continual encroachment of other people’s scope into your professional world. It’s easy for anybody to hop online and earn a cheap certificate or to sit through a few online classes and then brand themselves an “expert” in said material. Therefore, going deep into certain subjects is vital for your own differentiation. Don’t succumb to the temptation of choosing appearance over substance. You need to really learn something, then stick to what you know.

Thoughts for Specialists

Armed with the knowledge above, specialists need to ask themselves important questions about the nature and scope of their work:

Are you learning skills that are actually transferable to new environments or are you just becoming an expert in the dynamics of your current company?

If forced to find a new job tomorrow, how will you prove to potential employers that your previous success is replicable? How will you prove it to yourself?

If you’re a specialist, is it because you intentionally chose to be so or was it simply a means to another end?

This final question is important.

I am sober to the fact that not everyone’s career goal is to maximize earnings or, god forbid, become a manager. In fact, my instinct is that most specialists pursue specialism because they have a real passion for that specific niche of medicine, software, media, construction, and so on. This is so admirable and no doubt pays dividends that cannot be captured in academic studies or labor data.

However, these same specialists would do well to take a page from their generalist colleagues' playbook and at least make a small effort to diversify their skillset a little; at least enough to ensure that the smallest change in technology, economy, or trend does not take them out. Getting curious about other disciplines and submitting oneself to learning uninteresting things can be a chore; but it is the extraneous work that must to be done in order to protect your passion. No basket deserves all your eggs, even if you really love that basket.

Organizational Considerations

Lastly, on an organizational level, this research gives executives, managers, and hiring decision-makers a lot to think about; and I plan to write about some of the ramifications in future newsletters. Take, for instance, this little nugget:

Although jobs categorized as specialists’ positions should (ideally) have focused on a single specialized function, 36.2% of the listings for specialists covered two or more unrelated functions. In comparison, 98.8% of the ads for HR generalists required candidates to have two or more (often unrelated) functional skill sets.

Now, companies are inherently complex structures, so there will always be an infinite number of places to seek and find opportunities for improvement. But from a strategic perspective, I think that nailing the generalist-specialist mix (as opposed to thoughtlessly surrendering to the generalist bias) and really dialing in the management processes for facilitating their wellbeing can yield incredible results.

Filling the company with the right mix of wide and deep people will ensure that the company itself grows wide and deep — which in turn produces surprising, inimitable, and valuable innovations, as opposed to a generic, cookie-cutter results. Moreover, accommodating both types of individuals is itself a type of diversification, keeping the organization in a state where they are capable of both exploiting the stable times (this is what specialists do) and navigating the uncertain times (generalists) with equal strength. Yes, optimizing for flexibility is essential, but it’s a myth that it doesn’t come with trade-offs.

Find the right mix, assess it frequently, and make sure to steward the advertising, interviewing, hiring, onboarding, and task assignment processes with fidelity to that ratio. The result is happier employees and a more productive business unit.

Conclusion

Many of the studies I quote are behind academic paywalls that my MBA program grants me access to. Although my conscience prevents me from sharing the full downloaded articles, I thought it would be appropriate to share the page where I copy and pasted some of my favorite parts of the studies. You can find that here. I would love to know your thoughts.

Thank you all for reading this week’s newsletter; please let me know if it was helpful to you in any way. If you have not yet subscribed, please do so now — it would absolutely make my day and I promise you can always unsubscribe later (although I know you won’t want to)!

Curiously yours,

Bradley

Great work as always! I’m curious what you’ve uncovered on the taxonomy between generalist and specialist in your research. Is it role-dependent, individual-dependent, or a mixture of both? If role is a primary signifier, then which roles fall into which buckets?