Between the Lines of the Org Chart

An easy framework for understanding who needs who in a change or transformation initiative

I’m a sucker for a good organizational turnaround.

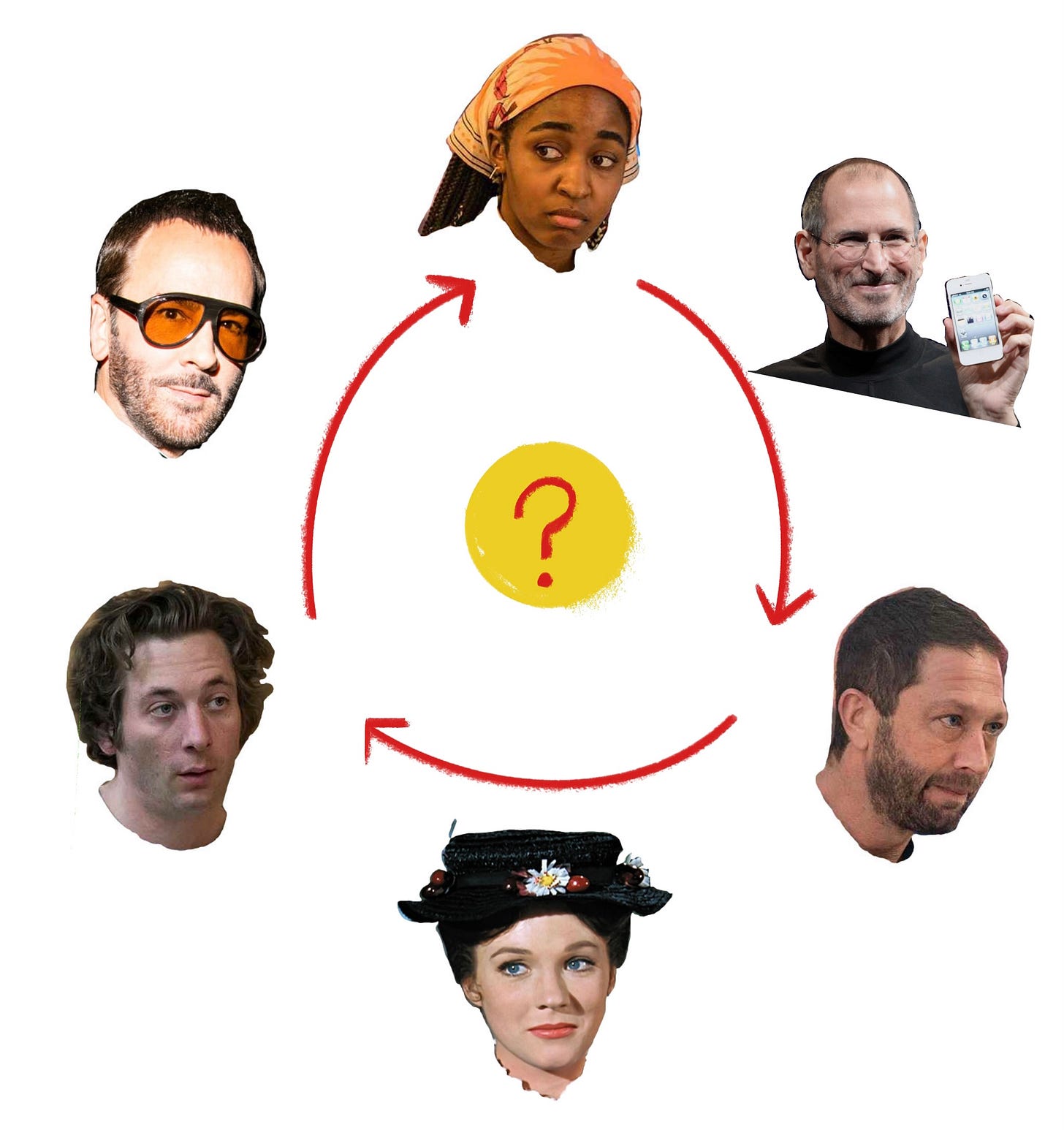

Throughout the last century, only a handful of exceptional individuals have successfully earned a place in the Business Hall of Fame by reversing corporate entropy and restoring a declining institution to former glory. Lee Iacocca at Chrysler, Tom Ford at Gucci, Steve Jobs at Apple, and Jack Welch at General Electric to name a few. If these change agents had an archetype — and I know this seems counterintuitive — I would argue that it's Mary Poppins. That is, a slightly vain figure who floats in from the outside world with a seemingly endless bag of tricks and oppressive standard of excellence. She disrupts the malaise of the household, reorders the interpersonal dynamics, and, quite literally, makes them take their medicine. Her magic, and the magic of the change agents she represents, is not the hammerspace or levitation. Rather, it's her knack for opening the minds of clients to new possibilities and giving them the confidence to be fearless and self-directing.

I argue that these aren’t just underdog stories. They’re redemption stories. Whether born from history or Hollywood, turnaround tales are a rich cocktail of hope, promise, and talent that illuminates the nature of successful comebacks. People gravitate towards these stories because we love knowing that second chances are not just possible, but plausible. And while the familiar zero-to-hero tale speaks of ambition and triumph, turnarounds speak to recovery and continuity.

The Best Turnaround Tale on Television

I spent my last weekend before school binging a TV show about this very topic. Unlike the classic Mary Poppins tale, this story is making waves for its raw and anxious depiction of transformation. It foregoes the usual emphasis on a singular genius’ efforts, and focuses instead on the difficulties of collective change, as well as the complicated nature of found family. I’m in love with this show and felt inspired to write at least one newsletter analyzing it from an organizational and management perspective. Specifically, I want to chat about a framework I have found personally useful for collaboration and decision-making.

If you have not yet watched Season 1 and 2 of The Bear, I suggest you do so at your earliest convenience. I have kept the following spoiler-free, so you can continue reading without fear. A little warning though, should you decide to give the show a try: it is guaranteed to raise your blood pressure.

(*Disclaimer: The following post builds on non-original material. These categories were not invented by me, but have been tweaked, named, developed, and processed by me over time. Despite my best research, I haven’t found the original source. If you know, I would be thrilled if you could share so that I can properly attribute it to the maker.)

Summary of The Bear

The Bear is a fictional FX/Hulu series about the efforts of a globally renowned chef to revive a darling but dying restaurant previously owned by his recently deceased brother. The 2022 dramedy has earned a stunning total of 13 Emmy nominations and 10 wins. The show is a masterclass in storytelling and every episode is a feverishly intimate window into the pressure cooked messes of a ragtag group of employees framed by a gritty, yet undeniably romantic, Chicago backdrop. While every employee has their own character arch, I offer that The Bear revolves around three primary characters:

Carmy — the main protagonist, owner of the store, and veteran chef who once ran the world’s greatest restaurant. He is serious, elusive, and excellent at what he does.

Richie — longtime restaurant employee, Chicago native, and people person. Richie was best friends with the previous owner, Carmy’s brother, before he passed away. Richie is all passion and no polish, which often puts him in conflict with others. I like the way he puts it: “I’m not like this because I’m in Van Halen. I’m in Van Halen because I’m like this.”

Sydney — a young, funny, and formally trained chef with uber amounts of talent. She comes to the restaurant in order to learn Carmy’s ways and redeem herself from a previously unsuccessful catering start-up.

An Alternative to the Org Chart

The relationship of this trio not only makes for good television, but taps into a dynamic that exists in almost any group pursuing a business objective. In a team, people often fall into one of the following three categories: the one with the most essential skill, the one with the most history, and the one with the most skin in the game. When a problem or opportunity is introduced, knowing the category you or your colleagues fall into is a good predictor of how the team will self-organize. Let’s break it down more cleanly before applying it to the show.

The objective is the centerpiece that orients the group and gives them something to strive for.

The one with the most essential skill is the one with the ability needed to execute on an action and move the group toward its objective. This person defers to the one with the most history for knowledge and direction. The others rely on them to carry out the mission.

The one with the most history is the person with the most experience, most research, or most previous participation. These people will defer to the one with the most skin the game, since the latter has the most to lose should the objective not be accomplished. The others rely on this person for counsel.

The one with the most skin in the game has the most at stake and will defer to the one with the most essential skill, since the latter is the one “pulling the trigger” and doing the critical work. The others rely on this person to keep them accountable towards the consequences.

If you are able, take a moment and think about how this plays out in a team you are, or have been, a part of. What role have you often played? Who were you required to trust in? Who deferred to whom during moments of decision?

Org Charts and Frameworks Aren’t True, Just Necessary

This framework is not a formula — it's a heuristic. I like to think of it as an alternative way of evaluating collaboration. It is definitively not a personality typology — it is situationology. These roles are inherently fluid. Members of the same team shuffle between the different categories from one objective to the next, and can even occupy different categories when there are multiple objectives in play. The category descriptions rarely fit neatly over literal job descriptions, which is why I find this to be such a valuable resource. Org charts are useful for giving a snapshot of a company’s formal lines of hierarchy, but they don’t adequately capture the dance of responsibility, deference, and reliance which takes place in the blank spaces.

Let me be very clear. It is not that an org chart is wrong, only that it is limited. Org charts charts and frameworks are never true, only necessary. In real life, authority and trust are moving targets. If this has been your experience, I think you’ll find this tool useful.

Dynamics of Deference in The Bear

If we placed our characters from The Bear into the framework, it would look like this:

The objective is to take the restaurant from flailing to flourishing

The objective boils down (pun intended) to making good enough food to keep the store going. Remember, each individual might have unique personal incentives, but the overall objective is the end game that everyone is striving for.

Carmy — the one with the most skin in the game

Carmy is heavily invested in the restaurant both emotionally and financially. If it goes under, he not only faces over $300,000 of debt, but loses the last meaningful touchpoint with his beloved brother. He is a mastermind with ingredients, but doesn’t have the bandwidth to both manage the restaurant and keep the food coming out of the kitchen at a high level. He needs someone else to do one or the other. Enter the next player…

Sydney — the one with the most essential skill

Having been educated in a prestigious culinary school, Sydney becomes the head chef that Carmy puts in charge of the kitchen and entrusts with making their gourmet cuisine. She knows how to work a kitchen, but doesn’t know how to work this particular kitchen, which, like a lot of organizations, has devolved into a jigsaw puzzle of idiosyncrasies and non-standardized procedures. She needs someone with insider knowledge. That means...

Richie — the one with the most history

He knows the customers by name, why that one wall has burn marks, and who to call when the thingie breaks down… again. He has been there the longest, but doesn’t have as much at stake as Carmy (the one with the most skin in the game), which is why every shouting match — and there are many, many of those — ends with Richie acquiescing to Carmy.

Where To Start

The objective occupies the center of the diagram for a reason. It is the organizing principle. Every leadership book emphasizes the importance of getting your team on the same page, which requires communication, communication, and more communication. This is a well-known fact, so repeating it here feels redundant. However, redundancy is the key to communication, both on Substack and in teams. The best communicators know that they need to always be repeating themselves, since they realize that people live busy mental lives and don’t always hear words the way they are said. The best communicators also realize that they are themselves a mentally busy person and don’t always say things the way they intended to. That’s why they repeat themselves — because repetition is vital for communication. So if you’re a member of any team, be a good neighbor by repeating yourself. And did I mention that repetition is important to communication? Because repetition is very important for communication! Don’t be afraid to repeat yourself, I repeat.

It’s appropriate to highlight, however, that communication is not the sole responsibility of “leaders” or line managers. Communication is everyone’s privilege. The Bear actually has a brilliant nod to this fact, as one of the first and most effective habits they develop is yelling “corner” or “behind” when walking through the kitchen. Even more poignant, Carmy requires every order barked from team members to be acknowledged with a resounding “yes, chef.” This concept of receiving orders from someone else and addressing them with the honorable title of “chef,” irregardless of their role in the kitchen, becomes a motif in the show. Not only does it reflect the more egalitarian culture of the restaurant, but becomes the expected baseline level of respect they give each other, even in moments of extreme duress.

Trust

Of course, a team can be aligned around the objective and still misfire. We will look at the causes for some individual failures of the roles down below, but need to address a more fundamental component first: trust. This is something good communication and repetition can't solve. If the ball is consistently dropped even though everyone is seemingly clear on the objective, then it's highly probable the team doesn’t have an ample amount of confidence in their peers. This is because when trust is absent, individuals don’t defer to one another in the pattern laid out in the framework. Office politics, inherent bias, historic mishaps, or any other range of factors can convolute the relationship, making people gun-shy about leaning on a teammate in a productive way. Unfortunately, there’s no panacea for this, as each case is highly contextualized. Trust issues ultimately require candid conversations and maturity, for which there is no shortcut. Fixing this, however, needs to be a main priority. As Stephen Covey once wrote, teams can only move at the speed of trust.

What Each Role Brings to the Table (Pun Intended)

The one with the most skin in the game and the one with the most history might seem less valuable than the one with the most essential skill, but this is an incorrect analysis. Let’s break down why this is.

The person with the most skin in the game contributes important factors to the work: accountability, urgency, and the call to excellence. In The Bear, Sydney is occasionally tempted to let the standard of food fall in order to meet the demands of the customers. She needs Carmy to refuse to let the standards slip. He is wont to do so because of how much he stands to lose if the venture is unsuccessful. The participation of Carmy’s role is what ensures that the job gets done on time and is the best possible version of the work.

This can backfire in either direction, however. If the one with the skin in the game becomes overwhelmed or lacks trust in the others, they can easily devolve into micro-managers, naggers, or controllists. Similarly, the one with the most essential skills needs to faithfully maintain contact with the rest of the team or they will lose sight of the objective.

The most chaotic episode of Season One (if you’ve watched, you know which) is a perfect example of this relationship's breakdown. Sydney flexes her skills too much and sends out a dish before getting Carmy’s approval to put it on the menu, which ends up harming the entire team. Similarly, Carmy’s neurosis and fear of failure gets the best of him, and he dishes it out (pun intended again) on the staff in a borderline abusive way.

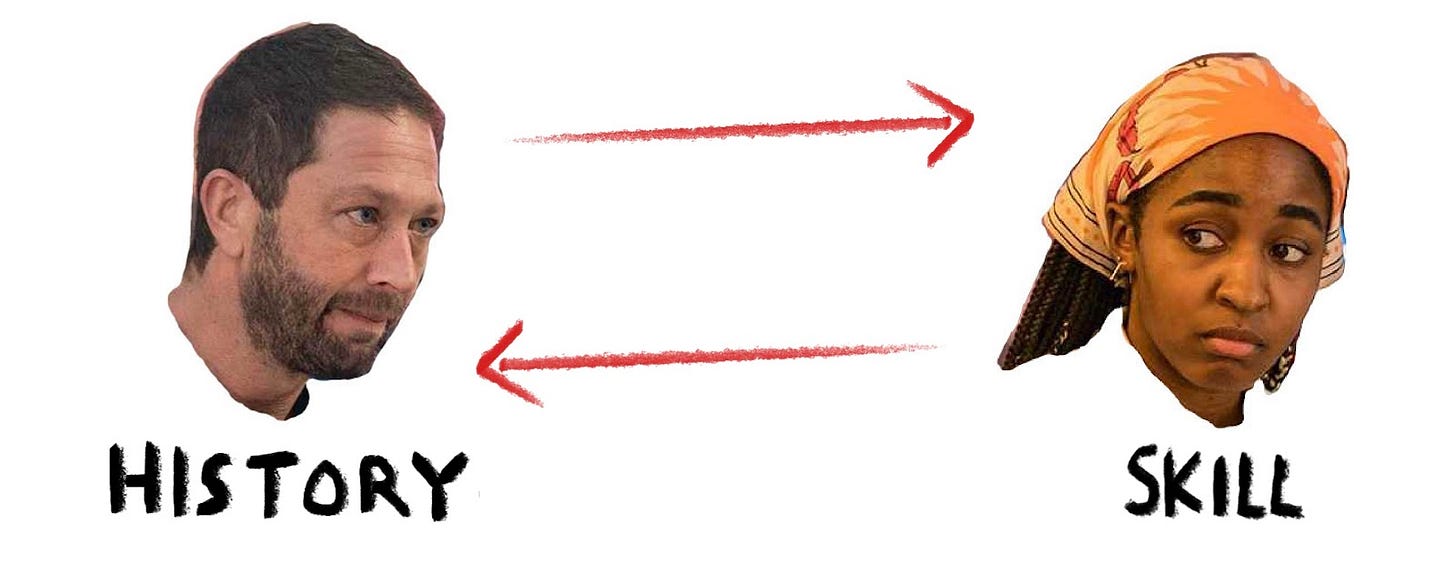

The dynamic between the one with the most essential skill and the one with the most history is also unbelievably productive and worth exploring. When you combine the capabilities of the former with the insight of the latter, you get a partnership able to make informed decisions with reliable and repeatable efficiency. Together, they know exactly where the bottlenecks in the process are and how to unstuck them, which update customers want most and how to create it, or the pain point for employees and how to relieve it. Together, they can reduce mountains into molehills.

On the flip, disagreement between these two produces organizational and personal frustration.

In a turnaround, the one with the most essential skill has to be humble enough to listen to the one with the most history in order to be guided by their experience. The one with the most history has to be okay with the organization changing on a fundamental level. This change often makes elements of their experience irrelevant and forces them to upgrade their skills in order to continue contributing. Provided they successfully upskill or reskill, they become the one with the most essential skill.

On Change In An Organization

In any transformation project, there will be some people resistant to change. It is vital that we understand it is not necessarily the ones that have been there the longest that resist it most. In fact, these people are often eager to shake up the status quo and begin growing. This is delicately and beautifully handled in The Bear through two non-primary characters, each who engage with the new owner via differing levels of fear, apprehension, and eagerness.

Still, the ones with greatest tenure are sometimes hard to onboard to the renewal effort. Executives do well to first examine whether or not the senior management is doing a good job communicating the story, vision, and benefits of transformation before writing off others’ reticence as mere traditionalism. There is an abundance of literature to support the notion that change is adopted more readily when executives listen, give away control, and let less senior employees help shape the new world.

The First Law of Intelligent Tinkering

Furthermore, I assert that it's reasonable if the person with the most history is resistant to change. Isn’t it logical that they would have a deeper connection to the old way and a truer appreciation of its value? Compassion and respect for this fact are fundamental components of human-centric management often missing from renewal efforts. While agility and speed are sexy advantages, the old mantra of “move fast and break things” has ultimately not withstood the test of time — even to those who coined it. Often, this is just technique rearing its ugly head. Instead, I prefer the attitude of Aldo Leopold:

“The first law of intelligent tinkering is to save all parts.”

In other words, a foolish person throws away anything they can’t see the value of. A wise person only throws away what they know for certain is worthless.

If you’re tinkering with an organization or a project, never make an irreversible decision until you have taken the time to understand why it existed as it was in the first place. Although no one should be expected to foresee every knock-on effect in a complex system, being thoughtful and inquisitive reduces the collateral damage wrought by reckless innovation. This is what the one with the most history helps avoid. They are an essential ingredient to responsible progress. (That’s my last cooking pun, I swear.)

Conclusion

Now that you are a little more familiar with the framework, take a moment to again reflect on the teams you are a part of. My hope is that it will cultivate a deeper appreciation for the unique contribution of your colleagues and streamline the choreography of participation which takes place beyond the pale of sacred org charts. If you agree, disagree, or have any observations and questions, please feel free to drop them in the comments. Don’t forget to subscribe and I hope to be in touch with you soon.

Curiously yours,

Bradley Andrews

Brilliant, bearish and cool. Go Bradley!